Many pop culture phenomena have made history, but something about Pokémon stands entirely apart…

On October 16, 2025, people waited in line to buy the latest Pokémon game, Pokémon Legends: Z-A. It didn’t matter how long the line was—all they wanted was to buy the game, play it, and experience the magical journey that every Pokémon game has to offer. (Myself included.) Young and old—the demographics didn’t really matter. Millennial Pokémon fans in their 30s or 40s, who still felt like eight-year-olds from the late ’90s, were showing their children the magical world of Pokémon. Gen Z fans in their 20s (or wrapping up their late teens) were ready to dive into the adventure, just like they did in the 2000s and 2010s. And Gen Alpha kids were gearing up to enjoy the new Pokémon journey, courtesy of their parents. All had one thing in common: they love Pokémon. As time goes by, no matter how old they get, the feeling of playing Pokémon never gets old. As a fellow die-hard Pokémon fan, I echo the same sentiment.

By the end of the first week, Pokémon Legends: Z-A had sold an impressive 5.8 million copies worldwide. This figure, announced by The Pokémon Company shortly after the October 16, 2025 launch, included sales across both Nintendo Switch and the new Switch 2 (with roughly half on the latter platform). Lines at stores, midnight releases, and massive digital downloads proved the hype was real—fans young and old couldn’t wait to dive back into Lumiose City. Never mind that this game is simply a continuation of Game Freak’s experimental Legends series, or that first-week sales were down compared to Pokémon Scarlet and Violet’s explosive 10 million units in just three days back in 2022 (a Nintendo record that still stands). Despite the dip—placing Z-A as the fifth-best Pokémon launch ever—these numbers once again proved just how popular and beloved the Pokémon franchise remains. Another year, another blowout success. No matter how many years go by, the popularity of Pokémon never seems to age. And with the franchise set to celebrate its 30th anniversary in 2026 (kicking off on February 27 with special logos, animations, events, and more announcements on the horizon), the question begs to be asked: Is Pokémon pop culture’s greatest achievement in history?

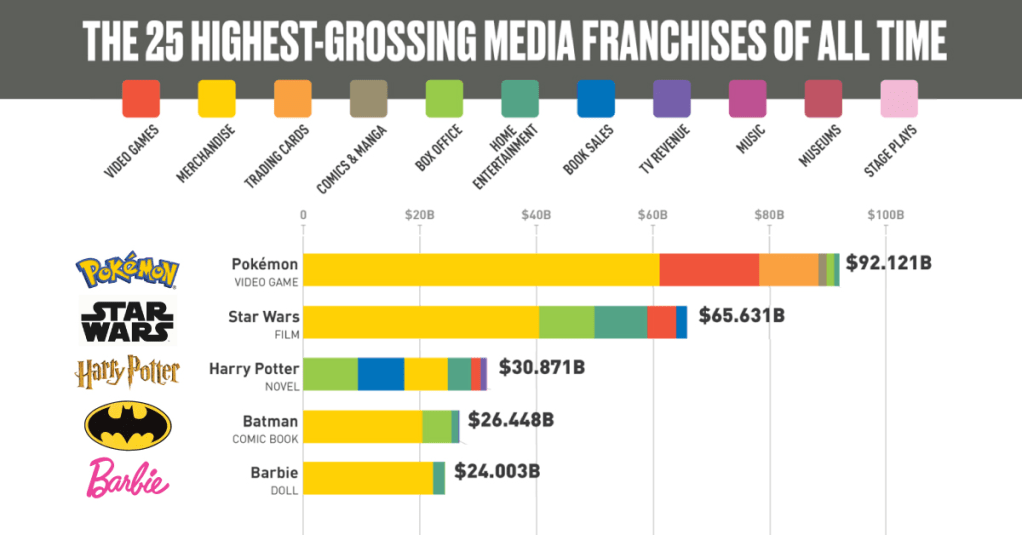

Many pop culture franchises have enjoyed tremendous success. Disney is known as an animation empire and has always summoned massive audiences. Other well-known pop culture icons—from Hollywood blockbusters like Star Wars to entertainment based on comics and art like DC, Marvel, and international phenomena such as Britain’s Harry Potter—also boast iconic status and huge followings. Yet, in spite of that, their popularity and fortune don’t even compare to Pokémon’s staggering $105–$288B lifetime revenue (with the highest estimates reaching $288 billion as of late 2025, including games, merchandise, trading cards, anime, and more). This makes the Pokémon franchise the highest-grossing media franchise in entertainment history, outpacing giants like Hello Kitty ($80–$88B), Mickey Mouse & Friends ($52–$70B), Winnie the Pooh ($48–$75B), Star Wars ($46–$70B), and the Marvel Cinematic Universe (~$30–$35B from box office alone, plus merch). Pokémon’s fans remain young at heart, it keeps gaining new generations of followers, and somehow manages to retain the old audiences who grew up with it from the very beginning in 1996. The recent launch of Pokémon Legends: Z-A on October 16, 2025—selling an impressive 5.8 million copies in its first week (with roughly half on the new Switch 2)—further proves the enduring power, even if lower than Scarlet and Violet’s explosive debut. So, for this article, I’ll be doing a deep analysis of today’s topic: Is Pokémon pop culture’s greatest achievement in history?

First, to understand Pokémon’s unprecedented domination in pop culture and its universal popularity—not just in Japan, but around the globe—its video games are consistent bestsellers, even if they’re often considered underwhelming. The trading card game (TCG) remains in constant high demand and stands out as the most popular TCG available, with over 75 billion cards sold lifetime (and massive ongoing print runs like 10.2B+ in recent years), despite scalper epidemics and packed trading card shows. Its merchandise sells 24/7 ($10.8B in 2024 alone, pushing lifetime merch past $90B+), and Pokémon-branded items can be found universally, anywhere you go—from Pikachu jets to manhole covers. The thing is, this overwhelming dominance didn’t start yesterday. It’s been a reality since the franchise launched in Japan on February 27, 1996 (as Pocket Monsters Red/Green), hit America in 1998, and the rest of the world in 1999—igniting “Pokémania.” The big question is: How did Pokémon get so big? Why was it so significant from the beginning—and still is today?

It’s Successful Launch in Japan (1995-1998)

Fun fact: Prior to Pokémon’s release, the franchise’s development was the textbook definition of “doubt turned into staggering success.” It took Satoshi Tajiri six grueling years for his passion project—initially pitched around 1990 after Game Freak officially formed as a studio in 1989—to “accidentally” explode into a global phenomenon. Tajiri’s dream suffered relentless setbacks: crippling salary shortages (he took zero pay, surviving off his father’s support), brutal glitches and endless development hell (nearly bankrupting Game Freak; five employees quit amid the chaos), and fierce skepticism from Nintendo executives (initial pitch rejection—they couldn’t wrap their heads around the quirky bug-collecting concept). Then, gaming legend Shigeru Miyamoto—”who you obviously know already”—stepped in sensationally as Tajiri’s mentor, championing the project, suggesting the genius dual-version format (Red and Green) to boost trading, and pushing it through Nintendo’s gates. Finally, on February 27, 1996, Pocket Monsters Red and Green launched in Japan for the Game Boy. Even then, hype was nonexistent—initial shipments were modest (~230,000 units)—and Nintendo remained deeply doubtful, especially with the seven-year-old handheld’s sales slumping rapidly (down to a low of ~$175 million globally in 1996 after peaking years earlier). Of course, they were spectacularly wrong: the games shattered expectations, rocketing past forecasts to sell over 1 million copies in Japan within months (1.04 million combined with Blue that year alone), becoming the best-selling Game Boy titles ever (31+ million worldwide for Gen 1), surging hardware demand, and igniting a pop culture wildfire that stunned even Nintendo’s masterminds.

Wait—there was something oddly different about Pokémon that not even other Nintendo franchises could match. After the franchise’s blowout success, Pokémon doubled down on risks with unprecedented marketing strategies no prior Nintendo IP had attempted. First up: the Trading Card Game (TCG), officially launched in Japan on October 20, 1996 (with the “1st Starter & Expansion Pack/Base Set”), preceded just five days earlier by promo Pikachu and Jigglypuff cards distributed via the November issue of CoroCoro Comic (released October 15)—marking the very first playable Pokémon TCG cards ever printed. Higher-ups doubted it heavily—TCG was niche in Japan, with Magic: The Gathering as the only real standout (Pokémon would later surge to #2, but collectible TCGs were still a fledgling market overshadowed by traditional games like hanafuda). Pokémon pushed through anyway—and like the video games, the TCG exploded into an instant success, despite mainstream media largely ignoring the launch (except CoroCoro). While CoroCoro Comic—read by roughly 1 in 4 Japanese elementary school kids and a powerhouse for hype with exclusive promos—gets major credit, the bigger picture was Pokémon’s built-in momentum from the smash-hit games and early merchandise, fueling 499 million cards printed by March 1998 alone (a staggering print run that underscored the frenzy).

Finally, the anime. The Pokémon animated series wasn’t just a pivotal part of the franchise’s sustained success—it became the single biggest piece of media to spread awareness of Pokémon, not only across Japan but worldwide, introducing the brand to countless millions who had never touched the games or cards.Similar to the games and TCG before it, the anime faced heavy opposition from many higher-ups—including Tsunekazu Ishihara (then-president of The Pokémon Company)—who feared it would accelerate the “consumption” of the property, burning through the fad too quickly and shortening its lifespan. Ishihara was especially worried that if the anime eventually ended, fans might assume the entire Pokémon franchise had concluded and simply move on to the next big thing (particularly with the highly anticipated Gold and Silver games still in development at the time).Nonetheless, the genius of Masakazu Kubo—deputy editor of CoroCoro Comic who became the anime’s executive producer—championed the idea relentlessly. Kubo leveraged his proven track record with the wildly successful Mini 4WD anime Bakusō Kyōdai Let’s & Go!! to convince the skeptics, including Ishihara himself. To ease concerns about overexposure, Kubo promised a modest initial run of 1.5 years—an unusually long commitment for a debut anime series, requiring significant upfront investment in staff, animation, and production.Eventually, the Pokémon anime premiered on April 1, 1997, on TV Tokyo under the title Pocket Monsters. It quickly became one of the most important and historic milestones in anime—and indeed in global animation history. The series has now surpassed 1,300 episodes (spanning over 25 years and multiple generations), has been broadcast in 192 countries and territories, and served as a true “gateway” to anime and manga for entire generations of viewers outside Japan. Its theatrical films amplified the impact even further: Pokémon: The First Movie (1998 in Japan, 1999 in the U.S.) shattered records by achieving the highest-grossing opening weekend for any animated film in U.S. history at the time, proving the anime’s massive cross-cultural appeal and helping cement Pokémon as a lasting global entertainment empire.

What I’ve noticed about Pokémon’s blueprint for success? It went all out—not just as a video game franchise, but expanding its franchise to other types of media entertainment. Because of Pokémon’s astounding success in Japan, the franchise enjoyed an already-built hemisphere of pop culture dominance in Japan in just the span of a year. Truly an unprecedented achievement for a franchise—not just at the time, but even by today’s standards. So, because of Pokémon’s high momentum, its success was emulated worldwide… The question is, how?

American Success And Birth of Pokemania (1998-2000)

Because of Pokémon’s already established success in Japan, the true test for the franchise was its performance outside Japan—and Nintendo of America’s president (and founder), Minoru Arakawa, was the first key executive to show strong interest in bringing it to the United States. Arakawa first encountered the games at Shoshinkai 1996 in Japan (November 22–24), where he played early titles and immediately saw their potential. I’m sure you’re tired of hearing the word “doubt” by now, but hilariously, it reared its head once more. Nintendo of Japan (NOJ) was highly skeptical about localizing Pokémon for the States, believing American kids lacked the attention span and interest for RPGs—a genre that remained niche in the U.S. at the time and was rarely known outside hardcore gaming circles. Most American players preferred fast-paced action games, sports titles, and realistic graphics, in stark contrast to Japan’s fondness for deep characters and intricate plots. Pokémon was also dismissed as too “cute,” lacking broad appeal to young U.S. children.

In fact, the project caused so much concern that NOA briefly considered redesigning the Pokémon to “beef them up”—proposing edgier, graffiti-style art, more muscular creatures, and even a bizarre Pikachu resembling “a tiger with huge breasts” to boost “coolness.” Arakawa rejected these mockups outright, deeming them a failure, especially since the anime was already in production back in Japan. Very few Japanese media properties had succeeded in America without heavy “Americanization,” and even then, results were mixed—Sailor Moon’s early U.S. run in the mid-1990s is a prime example of a failed investment, plagued by poor marketing, awkward time slots (like weekdays at 9:00 a.m. or 2:00 p.m.), heavy censorship, and low ratings that led to quick cancellation. Despite negative pre-launch research and feedback from both NOA employees and American kids, Arakawa ignored the doubters, pushed forward, and greenlit an enormous marketing budget—reportedly $50 million or more (equivalent to about $96 million in 2024 dollars), rivaling the Nintendo Entertainment System’s 1985 launch.

Later, Alfred R. Kahn (often called “Al Kahn”), Chairman and CEO of 4Kids Entertainment (love him or hate him), played a major role in bringing the Pokémon anime to America—securing licensing rights outside Asia, personally financing the English dub and syndication, and broadcasting it via 4Kids TV. According to both Arakawa and Kahn, it was a mission to triumph over snobbish Western prejudice against foreign animation. Not to mention the massive promotional spending by both NOA and 4Kids. In spite of reluctance from TV networks and advertisers—not to mention the high stakes, as a flop could have sunk 4Kids—stations eventually aired Pokémon, but in unfavorable early-morning slots around 6:00–6:30 a.m. Eventually, on September 7, 1998, Pokémon officially premiered in syndication across the U.S. Around that same time, Nintendo partnered with Wizards of the Coast (creators of Magic: The Gathering) to launch the Pokémon Trading Card Game (TCG) nationwide on January 9, 1999 (with pre-sales in select stores starting in December 1998). So, what happened next?

Pokémon exploded—its popularity didn’t just grow; it literally invaded every aspect of American life, from playgrounds and schoolyards to shopping malls and living rooms. Mainstream media outlets across the country were buzzing with reports of “Pokémania,” describing it as a cultural phenomenon unlike anything seen before.The animated series quickly became the highest-rated syndicated children’s show on weekdays, triggering intense bidding wars among major networks. When it premiered on Kids’ WB! in February 1999, the debut episode drew massive viewership and became the most-watched premiere in the network’s history, holding the number-one spot for an astonishing 54 consecutive weeks.The video games sold nonstop—Pokémon Red and Blue flew off store shelves almost immediately after launch, while the Pokémon Trading Card Game exploded in popularity, with billions of cards printed and sold worldwide in a very short time. Merchandise was everywhere: toys, clothing, backpacks, lunchboxes, and more, generating hundreds of millions of dollars in retail sales within the first year alone.Then came Pokémon: The First Movie in November 1999. Despite receiving harsh reviews from many critics, who called it little more than a glorified commercial, fans packed theaters to see it. The film became the highest-grossing anime movie in U.S. history at the time, earning tens of millions domestically and proving the franchise’s massive fan-driven appeal. The overall impact was enormous. Pokémon delivered a dramatic surge in Nintendo’s profits during a challenging period, helping the company recover financially and boosting Game Boy sales significantly. At the same time, Nintendo was losing ground in the home console market to Sony’s dominant PlayStation. In many ways, Pokémon served as a powerful reminder that innovation—through creative, portable, collectible gameplay—still thrived within Nintendo, even as they no longer held the crown in living-room gaming.

Because of this explosive success, the term “Pokémania” was coined to describe the unprecedented craze. Pokémon became a sensation in America unlike anything seen before—a cultural juggernaut that infiltrated playgrounds, classrooms, and living rooms. The franchise grew so popular that its frenzy sparked widespread controversy. Kids became so obsessed that some self-proclaimed “experts” warned parents to steer clear, decrying it as overly commercialized and manipulative, with its relentless “Gotta Catch ‘Em All!” marketing accused of fostering unhealthy consumerism and materialism in children. It drew fire from social and religious groups: evangelical Christians branded the series “satanic” and demonic, claiming it promoted witchcraft, evolution, and summoning spirits through battling creatures (echoing the era’s lingering Satanic Panic), while others slammed it for violence and inciting behavioral issues. Things escalated to absurd levels with real-world incidents—fights, thefts, and even stabbings over rare trading cards at school—prompting hundreds of schools nationwide to ban Pokémon cards outright to curb disruptions, bullying, and “gambling”-like trades where older kids swindled younger ones out of valuable holographics worth up to $30. The anime faced its own backlash, criticized for lacking the sophisticated, fluid animation of Disney films and dismissed by detractors as “cheap Japanese animation”—despite being produced by OLM Inc., one of Japan’s largest and most respected anime studios. Some even called it a blatant cash-grab ripping off the “monster kid” genre like Ultraman or Godzilla. The fad loomed so massively that South Park parodied it in the episode “Chinpokomon” (Season 2, 1998), satirizing the hysteria with a plot where a scheming Japanese toy company uses addictive toys to brainwash American kids into an invasion force—co-creator Matt Stone later called the phenomenon “scary-big.” Hilariously, an op-ed in New Zealand’s The Dominion Post savagely quipped: “The backlash, which seems largely confined to the United States, may be no more than the sound of the world’s leading cultural imperialist gagging on a taste of its own medicine.”

Eventually, the intense Pokémania craze of the late 1990s and early 2000s began to fade by the early 2000s, with the decline becoming noticeable after Pokémon Gold and Silver (released in 1999-2000), as the original wave of hype naturally subsided—kids grew older, peer pressure labeled it “childish,” and the initial novelty wore off. The franchise remained solidly popular among core fans and continued to sell well, but it no longer dominated mainstream culture with the same feverish intensity. By the launch of Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire in 2002-2003 (Generation 3), the mainstream “aura” had largely diminished further. Sales for Ruby/Sapphire (around 16 million combined) were strong but noticeably lower than Gold/Silver’s 23+ million, reflecting a shift where Pokémon transitioned from a global phenomenon to a reliable, dedicated gaming franchise rather than a ubiquitous cultural obsession. Pokémon Diamond and Pearl (2006-2007, Generation 4) sparked a significant resurgence, often seen as a “second generation” of fans. These games introduced fresh innovations like the online connectivity of the Nintendo DS, a compelling region (Sinnoh), and beloved Pokémon, helping revitalize interest and drawing in both returning players and newcomers. Sales rebounded strongly, with Diamond/Pearl exceeding 17 million units. Sadly, Pokémon Black and White (2010-2011, Generation 5) marked a noticeable dip in overall popularity and sales (around 15-16 million combined), partly due to design choices like focusing solely on new Pokémon (no old ones until post-game) and mixed fan reception, leading to the lowest combined generation sales in recent history at the time. Pokémon X and Y (2013, Generation 6) felt like a prelude to renewed excitement, introducing stunning 3D graphics, Mega Evolutions, and a more accessible world on the Nintendo 3DS. While sales were solid (over 16 million), it helped set the stage for the franchise’s modern stability and ongoing appeal.

Despite these ups and downs, Pokémon has maintained remarkable critical acclaim, financial success, and a loyal global fanbase for decades. It has consistently ranked among the top-selling franchises, with generations building on each other through remakes, spin-offs, and evolutions in gameplay.Not to mention the massive boost from Pokémon GO in 2016, which exploded into a worldwide phenomenon, drawing millions of new players (and re-engaging old ones) through augmented reality. It recaptured some of that late-90s global frenzy, becoming one of the most downloaded mobile games ever, generating billions in revenue, and proving the franchise’s enduring power to capture cultural lightning in a bottle once again. To this day, Pokémon remains a beloved, stable giant in gaming and pop culture.

Pokemon Go And The Resurgence

In 2016—while the world was gripped by the intense U.S. presidential showdown between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, and the stunning Brexit vote that shook the United Kingdom—another massive cultural event unfolded: the launch of Pokémon GO on July 6.This augmented reality mobile game didn’t just become popular; it exploded into a global phenomenon, reigniting Pokémania on a scale not seen since the late 1990s. Suddenly, Pokémon was everywhere again, drawing in people from every walk of life—die-hard fans, casual players, kids, adults, grandparents, celebrities, and even people who had never cared about the franchise before. Streets, parks, landmarks, and malls filled with players staring at their phones, hunting for virtual creatures in the real world.The frenzy was wild and all-consuming. People played as if their lives depended on it—walking miles, driving to new areas, gathering in huge groups at “lured” locations, and talking about nothing else. Society as a whole was buzzing about Pokémon once more. The game broke every record imaginable: millions of downloads in days, servers crashing from overwhelming demand, and players literally everywhere. Of course, the massive hype brought back the same kind of chaos and controversy that had surrounded the original craze. There were reports of accidents (people walking into traffic or off curbs), robberies targeting players at remote spots, trespassing on private property, and even a few tragic incidents. Some workplaces, schools, hospitals, and public buildings banned the game outright. It sparked debates about safety, addiction, and the power of technology to influence behavior. Although the absolute peak of the madness faded after a few intense months, Pokémon GO achieved something remarkable: it reminded the entire world that the Pokémon franchise was still very much alive and thriving. It introduced millions of new people to the brand, brought back nostalgic fans, and proved the concept still had incredible staying power. Even today, years later, Pokémon GO remains hugely popular. Millions of players continue to explore, catch, battle, and trade every single day, with regular events, new features, and fresh Pokémon keeping the community active and engaged. The game not only survived the initial frenzy but evolved into a lasting part of modern pop culture.

So now the big question is: Does this make Pokémon the most successful pop culture franchise in history? Obviously, I’m not the type of person to judge other franchises from different media—especially if I have little to no knowledge of them—but let’s take a close, analytical look to see if any other franchise has enjoyed or achieved the same level of success as Pokémon.

Pokemon is The Highest-Grossing Media Franchise of All Time

As you all know by now, Pokemon is the highest grossing media franchise in history, with a total of $115 billion if it’s total value. As you can see from the chart, much of Pokemon’s revenue is through merchandise, followed by it’s video games, trading cards, and it’s home entertainment, box office, and manga. For a media franchise to nearly ace the criteria of what makes a franchise profitable is something else… Now, here’s the thing, I know most of you are probably thinking: “Well, yeah, it’s profitable because it simply is a good franchise”, and yeah, I agree, but, lets talk about the comparison and what I’ve noticed about Pokemon that media franchises can’t do.

First of all, Pokémon’s unprecedented success and massive profits stem primarily from the franchise’s genius marketing strategy. It positioned itself not just as a video game series—often criticized as “dangerously addictive”—but as a full-blown multimedia empire that expanded into every corner of entertainment in ways few others have matched.

What do I mean? Imagine if Pokémon had remained solely a video game franchise supported by a trading card game, with no anime or manga ever developed. Or if an anime adaptation did happen, it was just a short-lived show like those for Kirby or F-Zero—quick, limited-run series that never gained lasting traction. In that scenario, Pokémon might have stayed a niche hit exclusive to Japan, or later received the “Fire Emblem treatment” (popular among dedicated fans but never achieving mainstream global dominance). Instead, the higher-ups doubled down, pushing Pokémon into unprecedented levels of media expansion—even surpassing what Nintendo’s flagship mascot, Mario, has accomplished.

The results speak for themselves: a long-running anime series that has aired daily (or in syndication blocks) worldwide for decades, introducing generations to characters like Ash and Pikachu; a Trading Card Game that remains hugely popular to this day, with billions of cards printed, enjoyable collecting mechanics, and competitive play that draws in kids and adults alike; plus extensive reach into manga, books, graphic novels, blockbuster movies, exclusive online specials, DVDs, Blu-rays, and—most crucially—an avalanche of merchandise (toys, apparel, plushies, backpacks, collaborations with brands like McDonald’s, Adidas, and UNIQLO). Merchandise has long been Pokémon’s biggest profit driver, often accounting for the majority of revenue (with licensed products alone generating tens of billions over the years, far outpacing video game sales in total lifetime earnings).

I’m sorry, but I don’t think any other franchise has ever launched with—and still maintains—such a brilliantly comprehensive marketing strategy. Pokémon literally pinpoints every profitable aspect of what makes a media empire thrive: emotional storytelling through anime, social interaction via trading cards and battles, collectible appeal, nostalgia, accessibility for all ages, and relentless cross-promotion across platforms.

Some legendary franchises like Star Wars, Superman, and various Disney properties have existed for more than half a century (or even a full century in some cases), yet in just a few decades since the late 1990s, Pokémon has overtaken them in total revenue. The franchise stands as the highest-grossing media franchise of all time, with lifetime estimates ranging from over $100 billion to $150 billion or more (depending on the source and inclusion of merchandise/licensing), fueled by consistent annual billions from games, cards, and products. And here’s the thing—it’s not slowing down anytime soon. With the series celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2026 (marking February 27, the original Japanese release date of Pokémon Red and Green), expect even bigger celebrations, special events, new releases, and collaborations to keep the momentum going strong.

Let’s take Disney as a prime example. We all know Disney stands as one of the most famous animated and entertainment companies in the world, and it has existed far longer than Pokémon. By the mid-20th century, Disney had already established itself as an empire, with that era often regarded as the company’s Golden Age—marked by timeless classics like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), and Cinderella (1950), which set the standard for feature animation and built a foundation of iconic characters, theme parks, and massive merchandising.

Although Disney took significant hits in the 1970s and 1980s following Walt Disney’s death in 1966 (a period of creative struggles, box office disappointments, and competition from other studios), the company staged a remarkable comeback with the famous Disney Renaissance (roughly 1989–1999). This era revived the studio through Broadway-style musicals based on well-known stories, starting with The Little Mermaid (1989) and peaking with blockbusters like Beauty and the Beast (1991—the first animated film nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars), Aladdin (1992), and The Lion King (1994, which became one of the highest-grossing animated films ever at the time, earning over $968 million worldwide). Films like Pocahontas (1995), Hercules (1997), Mulan (1998), and Tarzan (1999) continued the momentum, blending stunning animation, memorable songs, and emotional storytelling to dominate the box office and earn critical acclaim.

This was followed by an experimental phase in the 2000s (with more CGI integration, like Lilo & Stitch (2002) and Bolt (2008)), before enjoying another major revival in the 2010s—fueled by hits like Frozen (2013, the highest-grossing animated film for years), Zootopia (2016), and Moana (2016)—along with the acquisition of Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, which expanded Disney’s empire into live-action blockbusters, streaming, and theme park attractions.

Now, let’s talk about Star Wars and how the franchise has existed since 1977, with the original trilogy released between 1977 and 1983 (A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi). These films revolutionized sci-fi cinema, created a massive fanbase, and spawned an enduring cultural phenomenon through toys, books, and merchandise—even during long gaps between major releases. The series returned triumphantly with the prequel trilogy (1999–2005: The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith), which—love them or hate them—drew huge crowds and generated billions in box office and tie-in revenue. In the 2010s, under Disney’s ownership (after acquiring Lucasfilm in 2012 for $4.05 billion), the sequel trilogy (The Force Awakens in 2015, The Last Jedi in 2017, and The Rise of Skywalker in 2019) and spin-offs like Rogue One (2016) and Solo (2018) kept the saga alive, despite growing polarization among fans over creative directions, character choices, and storytelling. Even then, though it’s undeniably popular, the franchise has taken hits after hits—such as mixed reception to certain entries, box office underperformance for Solo, fan backlash, and challenges in maintaining consistent momentum amid streaming shifts and cultural fatigue.

Now, let’s talk about DC and Marvel. We all know these two aren’t just pop culture phenomena—they’re arguably America’s most successful pop culture icons in history. While many might point to timeless figures like Mickey Mouse or Darth Vader as even bigger, I’d argue that the creation of superheroes like Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, and Captain America stands out as even more impactful. These characters have enjoyed extensive media expansion across movies, a massive library of comics (their original source material), video games, merchandise, TV shows, and a fiercely dedicated global fandom.

What sets them apart is the aesthetic—those iconic costumes, powers, and moral dilemmas—combined with a passionate community that spans generations, from comic conventions to cosplay, fan art, and endless debates. Sure, Star Wars has achieved similar (and in some ways even greater) cinematic spectacle, massive merchandise sales, and cultural staying power since 1977, but let’s be honest: if people had to choose between Spider-Man or Darth Vader as their favorite icon, who would win? Most would probably pick Spider-Man—the relatable, web-slinging everyman who resonates deeply with everyday struggles, humor, and heroism.

Yet, despite the legendary history and historical significance of these franchises—many rooted in the early to mid-20th century—Pokémon overtook them all in just a few short decades. A simple video game series born in Japan toward the end of the 20th century, right on the cusp of the 21st, defied every odd stacked against it: domestic skepticism in its home market, initial international doubt from executives who feared American kids wouldn’t embrace its quirky RPG style, and the challenge of breaking into a world dominated by established giants.

What makes this victory so grand is that Pokémon wasn’t merely a video game—it was a meticulously crafted multimedia empire built against all expectations. Starting as a risky Game Boy project in 1996, it exploded through relentless expansion: the anime that became a global gateway, the Trading Card Game that turned collecting into a cultural obsession, blockbuster movies, manga, and an avalanche of merchandise that continues to dominate retail shelves worldwide. This strategy triggered Pokémania—a hysteria that shook the world, causing school bans, parental warnings, massive crowds at events, and even real-world chaos—proving its power to captivate entire generations in ways few could predict.

The achievement is staggering: estimates place Pokémon’s lifetime revenue at well over $100 billion (with some recent analyses citing figures as high as $115 billion or more, often topping comprehensive lists of highest-grossing media franchises), surpassing icons like Mickey Mouse & Friends (around $60–70 billion), Star Wars (roughly $46–70 billion), and the Marvel Cinematic Universe (tens of billions from films and merch). These older franchises built their empires over decades or centuries through films, comics, theme parks, and enduring cultural symbolism, yet Pokémon—launched in 1996—achieved dominance in a fraction of the time through bold, interconnected innovation and evergreen appeal.

That’s what makes Pokémon’s pop culture triumph so monumental. It didn’t just generate billions—it stole the spotlight from previous mediums that had defined older generations (like Disney’s classic animation or Star Wars’ cinematic spectacle), capturing a new one with portable gameplay, emotional bonds via the anime, and endless collectible fun. In doing so, it proved that a modern, adaptable franchise could rewrite the rules of success, turning doubt into an unstoppable legacy that shows no signs of slowing down as it approaches its 30th anniversary in 2026.

Pokemon’s Demographic Never Ages

One of the core strengths I’ve noticed about the Pokémon franchise is its endless, infinite power to not only generate new fans but also retain its older ones for years—even decades—to come. Many media franchises aim to do this through nostalgia, reboots, or ongoing stories, and while that’s often true, what sets Pokémon apart is something most others lack: a consistently young demographic at its core, continually refreshed with fresh, child-friendly entry points..

Of course, that’s not to say that Gen Z has no interest in franchises like Star Wars or media companies like Disney—and let’s not forget that big-screen entertainment like Marvel and DC movies remains strongly popular among younger audiences (though comic books themselves often tell a different story, with more niche, older readership).

Even so, there’s something I’ve noticed across most of these franchises: they suffer from one glaring issue that plagues their communities—an insane age gap and an aging fandom mostly filled with people from older generations (Baby Boomers, Gen X, and the oldest Millennials). A common problem is how these media giants struggle to consistently attract and retain new younger fans in large, sustainable numbers. People often point out how Star Wars feels dominated by Boomers, Gen X, and early Millennials who grew up with the originals or prequels, while newer content sometimes fails to fully hook Gen Z. Disney faces criticism for losing ground with younger audiences to other entertainments like anime and manga—it’s gotten so noticeable that the term “Disney Adult” was coined to describe grown-ups (often childless Millennials) who remain deeply invested in parks, merch, and nostalgia, sometimes seen as a sign of the brand skewing toward older, nostalgic fans rather than fresh young ones.

DC and Marvel haven’t struggled quite as much with Gen Z when it comes to blockbuster movies, video games, and other media expansions—the MCU especially pulled in huge crowds during its peak—but even here, the age gap is strikingly notable. Comics (the original source) tend to draw more adults, and every year, anime and manga seem to snatch up target audiences, pulling young viewers over to their side with fresh, relatable stories, diverse characters, and accessible streaming. This leaves the two comic book giants with an increasingly aging fandom that ultimately proves the point: without a strong, ongoing pipeline of very young fans, it’s harder to maintain the same explosive buzz they once had.

Pokémon, on the other hand, seems to suffer no such issue at all. Every year, the franchise gains new fans, enjoys waves of unprecedented growth, and tops the sales charts across nearly every form of entertainment. From blockbuster video games (with the series having sold over 489 million units worldwide as of early 2025) to strong TV ratings in Japan, a thriving and growing fandom, flocks of merchandise flying off shelves, an overwhelmingly popular Trading Card Game that’s still exploding in demand today, and constant expansion—Pokémon keeps delivering while effortlessly maintaining its older audiences and welcoming fresh waves of young fans, especially children.

This is the core strength that Pokémon has: a perfect, self-sustaining cycle of renewal. While many debate the quality of recent games (and yes, some fans have valid criticisms), why complain when they’re selling like hot cakes year after year? Besides, I’m sure many of us have done the same—grumbling about one entry but still lining up for the next because the magic endures.

And that’s another powerful strength: because of its timeless, wholesome appeal—the cute designs, the sense of adventure, the “Gotta Catch ‘Em All” hook—Pokémon doesn’t even need to worry much about potential collapses or major bumps that could harm it long-term. Unlike other media giants like Disney or Marvel, which have faced audience backlash, revenue dips, or criticism over “woke” issues and perceived quality declines (leading to ongoing struggles for stability), Pokémon stays remarkably steady. Sure, some argue the franchise occasionally dips in quality or takes risks that don’t land perfectly, but why worry when it generates billions of dollars annually? Why worry when a Pikachu plush or a Snorlax plush sells out everywhere, every year? Why worry when merchandise is literally everywhere in stores—even in the middle of nowhere? Why worry when people wait in line for the latest Pokémon game like they’re starving and it’s the last meal on Earth?

That’s the infinite power Pokémon boasts that no other franchise truly matches: relentless, evergreen success through youth renewal, nostalgia retention, and massive cross-media synergy. This is what I call a triumph for Pokémon—one no other franchise has ever been able to replicate quite so perfectly. Experts once said the craze would end soon… and well, here we are.

I’m 28 years old (turning 29 this year), part of the Advanced Generation and Diamond & Pearl era, and one thing’s for sure: I can’t wait for more Pokémon this year. Especially since the franchise is entering its 30th anniversary in 2026 (kicking off from the original February 27 release date). We’ve already seen the new anniversary logo, special teasers (like that adorable Fat Pikachu animation), and plans for big collaborations—think McDonald’s Happy Meals with exclusive TCG cards, Adidas sneakers, more LEGO sets, fresh merch waves, and plenty of surprises still to come. Big things are waiting… and the momentum feels unstoppable.

Now that’s what I call a triumph by a media franchise that no other pop culture franchise has ever been able to match—not just the ones we’ve discussed, but virtually every single one that exists in this world.

Pokemon’s Aesthetic Appeal And Cultural Influence

Perhaps what makes Pokémon’s global success so effective is largely tied to its aesthetic and cultural appeal—a timeless, wholesome design philosophy that feels instantly accessible and emotionally resonant for basically anyone young at heart.

What do I mean? The franchise’s appeal starts with how fully accessible it is to children—the primary target audience. Pokémon’s creatures are cute, colorful, and simple on the surface: big eyes, rounded shapes, expressive poses, and a consistent “kawaii” (cute) style that has evolved gently over generations without drastic overhauls. From the early pixel sprites of Gen 1 to the smoother, more rounded 3D models of recent games (like Scarlet and Violet), the aesthetic stays recognizable and inviting—never alienating new kids discovering it for the first time. This consistency in design, combined with bright colors, friendly characters, and themes of friendship, adventure, and growth, makes Pokémon feel like a safe, fun world perfect for young players.

Yet, the same qualities make it enduring for adults too. Many who started as kids in the late ’90s or early 2000s now play as grown-ups and feel a sense of youthful joy reignited—nostalgia for the simple magic of collecting and exploring, paired with deeper layers that reward maturity. The core mechanics (catching, training, battling) are easy for kids to grasp but offer endless complexity for older players: strategic team-building, competitive battling, shiny hunting, breeding, and meta-analysis. Game Freak innovates thoughtfully—introducing new features like Mega Evolutions, regional forms, open-world exploration, or quality-of-life improvements—while preserving the heart of what fans loved originally. They update old elements (remakes, returning Pokémon) without heavy retcons or pandering that erases the past; instead, they build on it, giving adults fresh reasons to return without feeling like the franchise has “grown up” too much or abandoned its roots.

Because Pokémon is fundamentally a video game series, it enjoys more creative freedom than many other media. Developers can experiment with mechanics, worlds, and stories as long as they stay fun and engaging—no strict narrative arcs, no need for cinematic spectacle, and no pressure to follow Hollywood-style structures that often demand reboots, live-actions, or sequels to beloved properties. This allows Pokémon to evolve organically: each new generation brings innovation (like dynamic weather in Gen 3, online features in Gen 4, or full open-world in recent entries) while keeping the familiar “catch ’em all” loop intact.

In contrast, many Western counterparts—especially Hollywood franchises—have largely given up on bold new ideas in favor of heavy nostalgia reliance. Remakes, live-action adaptations, reboots, and sequels to already-beloved IPs often feel forced, poorly executed, or overly focused on appealing to older audiences while neglecting to create compelling entry points for new, young fans. This can lead to fan backlash, ruined legacies, or declining interest when the nostalgia well runs dry.

Pokémon, though it has had its own ups and downs (design debates, quality critiques in some entries), avoids these pitfalls thanks to its successful, balanced marketing and design practices. It stays stronger than ever by prioritizing accessibility, consistency, and genuine innovation—proving that a franchise can appeal to kids without alienating adults, and evolve without losing its soul. That’s the real cultural triumph: an aesthetic and approach that keeps feeling fresh, inclusive, and timeless, no matter your age.

Speaking of design, that’s another key part worth exploring. Pokémon’s design stands out completely differently from most other franchises, especially when viewed from a non-Japanese perspective. One of the most effective weapons in its global success is its diverse, highly appealing aesthetic—a mix of cute, expressive, and endlessly varied creatures that feel instantly relatable and emotionally engaging.

When Pokémon first arrived in the West in 1998, anime and manga as mediums were still largely niche. Though they had begun growing in popularity during the 1980s and 1990s (thanks to titles like Dragon Ball Z on Toonami or early imports like Akira), they remained mostly confined to dedicated fans. Many people in the West had little to no idea what anime or manga even were—if they encountered it, they often dismissed it as “simple children’s cartoons” not worth taking seriously, even when the stories were far more mature or complex.

By the time Pokémon burst onto the scene, children around the world were suddenly exposed not just to an amazing video game series backed by a TV show and trading cards, but to a design language that felt completely foreign and refreshingly different from what they grew up with in Western cartoons. Pokémon’s creatures—like Pikachu’s big, sparkling eyes, rounded shapes, and expressive faces—embody classic anime/manga traits: exaggerated features that convey deep emotion, a sense of personality in every detail, and an aura of warmth that creates instant attachment. This “digital bonding” felt strange to many adults at first (some even called it oddly addictive), but for kids, it sparked genuine affection and imagination in ways traditional American animation often didn’t.

Japanese creators pour incredible dedication into characters and stories, giving them layers of relatability, humanity, and depth—even in fantastical designs—that surpass much of what Western cartoons achieved at the time. Pokémon didn’t just look cute; the designs evoked real emotional connections, making players and viewers feel like they were part of a living world. This appeal wasn’t accidental—it was amplified by Pokémon being rooted in anime and manga style, a medium that was just starting to gain global traction.

This shift became most evident in the mid-1990s, as seen in the 1994 BBC documentary Manga! (hosted by Jonathan Ross), which introduced British audiences to anime through Akira and other works. In it, fans highlighted how anime’s artistry, intensity, and maturity allowed it to do things Western cartoons like Scooby-Doo could never match—deeper themes, stunning visuals, and emotional impact that felt far beyond “kids’ stuff.” Pokémon arrived at the perfect moment: as anime began to win worldwide recognition, it pulled children in not as “just another cartoon,” but as something seriously different—vibrant, expressive, and innovative.

Pokémon’s success played a major role in accelerating anime and manga’s global rise. It served as a massive gateway, introducing millions to Japanese animation and comics in the late 1990s and early 2000s (alongside shows like Dragon Ball Z, Yu-Gi-Oh!, and Digimon). This paved the way for milestones like Spirited Away winning the Oscar for Best Animated Feature in 2003—the first (and so far only) anime film to do so—proving anime’s artistic legitimacy on the world stage.

In the years since, manga has exploded in global sales, often dominating charts that include graphic novels. In the United States, manga now frequently outsells traditional American comics (with manga making up nearly half or more of graphic novel sales in recent years), while in Europe, it conquers the market with little competition from Western comics. What once took decades for anime/manga to achieve, Pokémon helped accelerate in just two decades—turning a niche medium into a mainstream powerhouse.

Pokémon’s design wasn’t successful just because it was Pokémon; it was elevated by being part of the anime/manga wave, introducing the world to a visual language that felt fresh, human, and infinitely expandable. That “foreign” brilliance—expressive eyes, emotional depth, and cute-yet-powerful creatures—created an attachment that no other animation style matched at the time, helping spark a global domination in animation and comics that continues today.

A video game series with the structure and format like Pokémon—where you catch Pokémon, train them up, watch them evolve into powerhouses, battle your way to become the ultimate Champion, and embark on an epic adventure packed with rich lore (legendary Pokémon like the majestic Rayquaza as the epicenter of coolness, the god-like Arceus anchoring the universe’s creation myth, fierce rivals, loyal friends, and endless bonding moments)—all portable right in the palm of your hand? That’s not just a genius way to craft a video game; it’s practically a scientific invention future advanced civilizations will rediscover and marvel at as the pinnacle of interactive entertainment.

Love your Charizard as your unbeatable #1? Pat yourself on the back for conquering that brutal Tyranitar challenge? Get wowed by Rayquaza’s sheer dominance? Feel the awe of Arceus tying the entire lore together? Congrats—you’ve experienced the journey! And the magic repeats flawlessly across every generation ahead: from the classic Kanto thrill to the futuristic vibes of Scarlet and Violet (with its open-world paradoxes and Terastal phenomena) and the upcoming Legends: Z-A (promising a gritty Kalos reboot with urban exploration and time-bending legendaries). Each entry refreshes the formula just enough to feel epic and new, while honoring what made the originals timeless.

Have you ever wondered how Pokémon masterfully balances its audiences across boys and girls? It’s all in the franchise’s profound diversity and unisex appeal—no demographic skews heavily one way or the other. Pokémon sends a powerful message: regardless of who you are, you can become the Pokémon Champion and dive into the magic without any criteria, restrictions, or judgments based on your gender, background, or personality. Your choice, your team, your story—pick the fierce fighters, the adorable cuties, the strategic tanks, or whatever sparks joy. That’s the secret sauce of its universal magic.

Just look at Pikachu: the ultimate mascot that effortlessly charms young boys (with its electric zaps and battle prowess) and young girls (with its fluffy cheeks and endearing squeaks)—no questions asked, no preferred preferences needed. Pikachu doesn’t “belong” to one group; it unites everyone. Compare that to other media giants: Disney properties often lean heavily toward girls (princesses, sparkly tales, emotional sing-alongs), while DC and Marvel comics skew boy-dominated (gritty heroes, high-action brawls, power fantasies). This rigid gender divide limits broad appeal and creates fan silos.

Finally, perhaps Pokémon’s most unexpected and profound impact on global pop culture was the way it quietly introduced millions of young children—many of whom had never thought about Japan before—to Japanese culture in a deeply immersive, organic way.

I won’t dive too deeply here (this deserves its own full article someday), but the essence is simple yet powerful: kids who grew up playing Pokémon weren’t just catching creatures—they were absorbing elements of Japanese society, values, aesthetics, and worldview without even realizing it. Unlike many franchises that heavily Westernize or “blend in” to appeal to global markets (changing names, settings, or cultural references to feel more familiar), Pokémon stayed remarkably true to its Japanese roots, even with thoughtful localization for names, jokes, and sensitivities. The core remained unmistakably Japanese: the locations (inspired by real Japanese regions), the settings (traditional festivals, hot springs, shrines, cherry blossoms), the character values (friendship, perseverance, harmony with nature, respect for others), the mythology (drawing from Shinto gods, yokai, and folklore), the art style (kawaii yet expressive anime/manga influences), and the design philosophy that felt entirely different from Western cartoons.

Children, including myself back then, intuitively sensed this “East Asian” (specifically Japanese) origin. Pikachu’s big eyes, the rounded, emotive creatures, the emphasis on bonds and growth over pure domination—it all carried a distinctly Japanese flavor that stood out as foreign, exotic, and endlessly fascinating. As the old saying goes: “opposites attract.” Because Japanese culture is so homogeneous, collective, and different from much of the Western world, that very difference sparked undying curiosity—not just for a video game franchise, but for an entire country.

This wasn’t subtle. In a well-remembered 2004 interview at a Pokémon event filled with children, many kids openly declared that Japan was cool—they wanted to visit, not only for Pokémon Centers and Pikachu parades, but for the food, the technology, the anime, the manga, the trains, the cities, everything Japanese. Their excitement was genuine and unfiltered. Meanwhile, their parents—mostly Gen Xers who had come of age in the 1980s and 1990s—looked on with pride and nostalgia. They had grown up during Japan’s economic miracle and cultural explosion (the rise of Nintendo, Sony, Studio Ghibli, anime exports, and the “Japan as future” vibe), even as older generations sometimes viewed Japan’s rising dominance with economic anxiety or hostility. For these parents, seeing their children fall in love with Japanese soft power felt like a beautiful echo: the same cultural brilliance they witnessed in their youth was now being passed down, reborn through Pokémon.

Pokémon wasn’t merely a cultural import; it became a massive booster for Japan’s soft power at a critical time. The country had entered the “Lost Decades” of economic stagnation starting in the early 1990s—a period of deflation, slow growth, and self-doubt. Yet Pokémon (alongside other exports like anime, J-pop, and games) reminded the Japanese people that they could still create inventions that captivated the entire world. It proved that Japan could export not just technology or cars, but imagination, emotion, and wonder—and do so on a scale that reshaped global youth culture.

Above all, Pokémon gave birth to an entirely new generation of people who love Japanese culture with genuine passion. Countless fans today dream of visiting Japan one day—not just for Pokémon-themed spots, but to experience the real thing: the cherry blossoms in Kyoto, the neon streets of Tokyo, the quiet shrines, the ramen shops, the bullet trains. They study Japanese, watch anime, read manga, collect figures, and celebrate traditions because a little yellow mouse and its friends opened the door.

In many ways, Pokémon is often debated as Japan’s greatest pop culture invention of all time—a single franchise that achieved what few others could: massive commercial success, cultural ambassadorship, and enduring global love, all while staying authentically Japanese. It didn’t just entertain the world; it made millions fall in love with a nation.

The Official Animangemu Museum of “My Otaku Origins” How Kurai became, “Otaku_Kurai”.

To this day, Pokémon is still thriving worldwide—with tens of millions actively playing the games (over 489 million units sold lifetime), the Trading Card Game booming (75 billion cards printed, with 10+ billion in the last fiscal year alone), and Pokémon GO drawing 70–80 million monthly active users (spiking to 120+ million during events). Fans adore it across every continent, from competitive tournaments to casual park raids.

Thanks to its genius blueprint, Pokémon didn’t just revolutionize the video game industry (pioneering portable collecting, trading, and AR with GO’s 2016 explosion)—it shook pop culture to its core. It became the #1 highest-grossing media franchise ever (lifetime estimates $100–150+ billion, outpacing Hello Kitty, Mickey Mouse, Star Wars, and Marvel), turned Pikachu into a global mascot rivaling Mickey Mouse (ubiquitous in merch, parades, and icons everywhere), supercharged anime and manga’s worldwide boom (serving as the ultimate gateway, boosting manga to dominate U.S. graphic novel sales and paving the way for Oscars like Spirited Away), and shattered the Euro-American entertainment monopoly—propelling Japan’s soft power to new heights during its “Lost Decades,” making “cool Japan” a reality through authentic cultural export.

This is what I call pop culture’s ultimate triumph—a 1996 underdog that rewrote the rules, captured generations, and built an unbreakable empire.

This year, as Pokémon celebrates its 30th anniversary (kicking off February 27, the original Red/Green release), the hype is electric: a stunning new logo with Fat Pikachu animation, the Pokémon Day 2026 TCG Collection (out January 30), McDonald’s Happy Meals with exclusive cards (February–March), collabs with Adidas sneakers, LEGO sets, Uniqlo tees, and more—plus a massive Pokémon Presents showcase expected on the big day, teasing Gen 10, Legends: Z-A updates, Pokopia (Animal Crossing-style life sim on Switch 2, March 5), remakes, or wild surprises. Who knows what magic awaits? One thing’s for sure: the success train isn’t stopping anytime soon. Here’s to 30 more years of “Gotta Catch ‘Em All!”

And this, my fellow otakus, is my so-called “thesis”—or rather, my long-form article laying out the case for why Pokémon is pop culture’s greatest triumph of all time.

I know I’ll get disagreements, objections, and maybe even a few insults along the way. That’s okay—this is ultimately my opinion, passionately argued and deeply felt. At the same time, I tried my best to ground it in facts, historical context, sales figures, cultural milestones, and observable patterns that make the narrative feel as objective as possible. I genuinely believe this is the correct interpretation of Pokémon’s extraordinary journey, and the evidence speaks louder than any single counterargument.

Regardless of where you stand, thank you so much for reading this—the longest, most detailed article I’ve ever written. Whether you’re a day-one fan from the original Red and Green days, a Diamond & Pearl kid like me, or someone discovering the magic right now, I hope this piece reminded you why Pokémon has captured hearts for three decades and counting.

Here’s to the 30th anniversary in 2026—may the adventures, the catches, the bonds, and the sheer wonder keep going strong for many more years to come.Gotta catch ’em all.

Thank you again.

Thank you so much for reading this, and don’t forget to follow, like, and check out my socials for more Animangemu content!

‘Florida’s #1 Akiba-Kei!”

Discover more from Animangemu

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.